· Brian Dranka · Strategy · 8 min read

Data Product Strategy

How smart companies build products for every layer of their data

In 1854, John Snow mapped cholera deaths in London’s Soho district, creating one of history’s first data products. By plotting each death at the address level and adding just one more layer - the location of water pumps - Snow identified a specific pump as the outbreak’s source. As a result, that pump handle was removed, the outbreak ended, and modern epidemiology was born.

But Snow’s innovation wasn’t just collecting more data, it was understanding that the depth of his geographic data (location of both deaths and water pumps) when properly aligned with a specific use case (identifying disease transmission patterns), could transform public health policy. Today’s data product builders face a remarkably similar challenge, albeit with higher complexity: how to align the depth and breadth of available data with viable product use cases.

The Data Distribution Problem

Every data product suffers from what I call the “depth-breadth paradox.” Organizations typically possess a small volume of extremely detailed, rich data alongside a much larger volume of shallow, sparse data forming a long tail.

A few years ago I led a team of exceptional R&D scientists at Agilent Technologies who collectively ran around 1,500 experiments per year. On paper, we were data-rich. I could tell you extraordinary detail about any single experiment: the complete experimental design, instrument parameters, analytical results, quality metrics, even the ambient temperature during the run. But ask me a simple question about ALL our experiments and I’d have to manually dig through 1,500 individual files to find answers.

We had depth without breadth. Each experiment was a deep well of information, but the wells weren’t connected. Only in a few cases did we have the right metadata structure to link experiments together into a powerful unified dataset. This wasn’t a technology problem, it was a fundamental mismatch between how scientific data gets created (one careful experiment at a time) and missed opportunities for how to consume it (in aggregate patterns). The realization that hit me wasn’t that we needed better data management, it was that we needed to accept this distribution as reality and build different products for the data we actually had, not the unified dataset we wished we had.

This tiered thinking represents the key insight for modern data product development: success comes not from having complete data, but from intelligently aligning use cases with data availability. The goal isn’t to build one perfect product, but to create discrete product classes that match your data distribution.

How Each Data Layer Creates Its Own Market

Let’s examine a few examples form pharma. When Genentech developed Herceptin in the 1990s, they didn’t have comprehensive genomic data for all breast cancer patients. What they had was deep HER2 expression data for a subset of patients. Rather than waiting for universal coverage, they built their entire product strategy around this data depth, creating the first targeted cancer therapy and fundamentally changing oncology treatment paradigms.

Today’s biomarker-driven medicine demonstrates how different data depths serve distinct, equally valuable markets. Consider a modern multiplex biomarker dataset. At its most streamlined level, you might have simple presence/absence calls for specific biomarkers. This focused data powers one of healthcare’s most valuable applications: companion diagnostics that guide treatment decisions. A binary report telling physicians whether a patient expresses PD-L1, for instance, directly determines eligibility for immunotherapy - a multi-billion dollar market with transformative patient outcomes. Adding more complexity to this use case wouldn’t improve clinical decision-making; it would add cost and interpretation burden without changing treatment protocols.

But importantly, different data depths enable entirely different products for different users. A multiplex biomarker panel with H&E imaging and co-location analysis is necessary for computational biologists developing next-generation therapeutics. Patient demographics layered onto biomarker data enable population health studies for payers and health systems - another multi-billion dollar opportunity. Longitudinal medical records with comorbidities and treatment histories support yet another product class for clinical researchers and drug developers.

The key is recognizing that these data products aren’t hierarchical. Deeper data isn’t automatically “better.” Each depth serves a specific use case and market optimally and can be valued accordingly. The physician treating a patient today needs fast, clear, actionable information. The computational biologist developing tomorrow’s diagnostics needs rich, complex datasets. Trying to serve the physician with the comp bio data would be as misguided as giving the scientist only binary outputs.

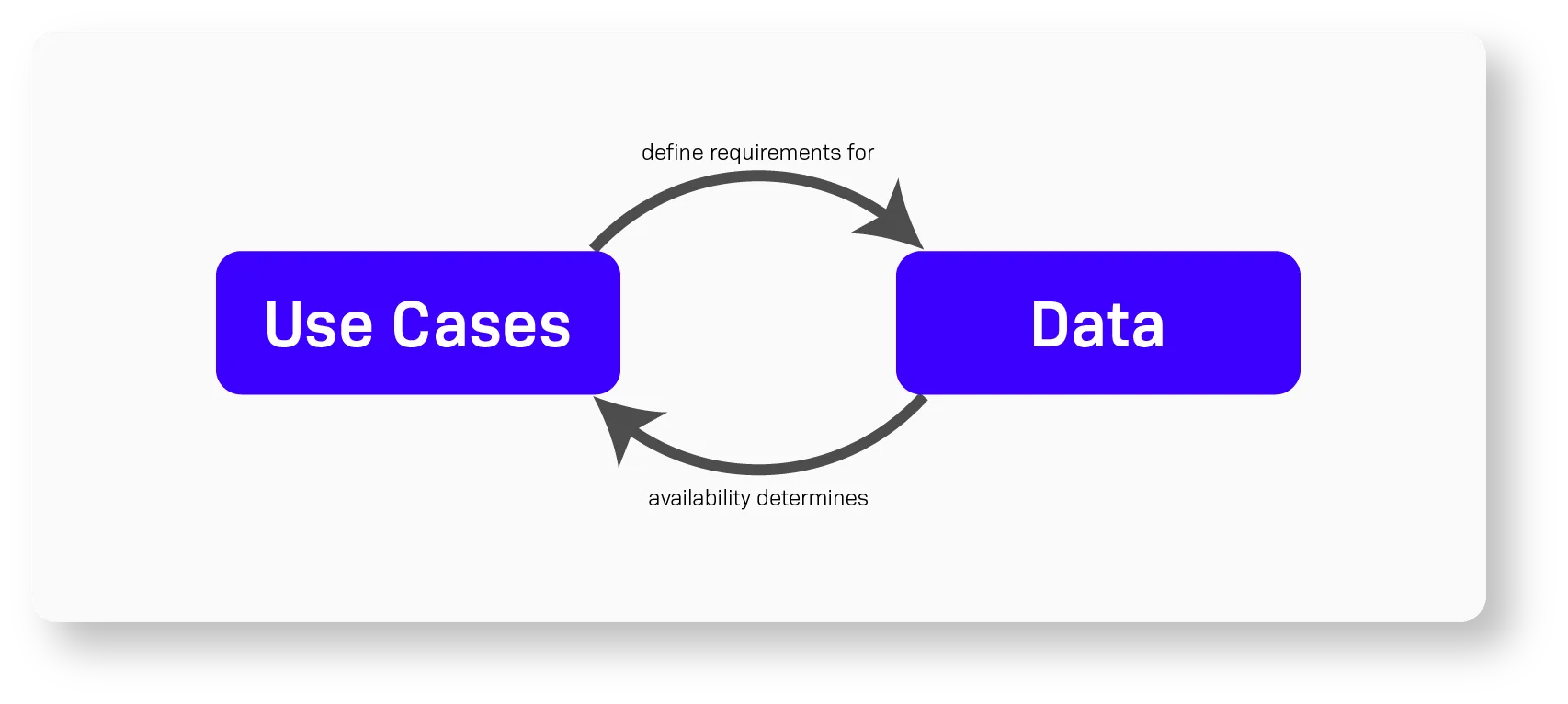

Breaking the Use Case-Data Deadlock

The fundamental challenge in building data businesses lies in a circular dependency: use cases define data requirements, but available data constrains viable use cases. This tension creates a strategic deadlock. The path forward isn’t to ‘solve’ this loop, but to break it with a strong, top-down business conviction. Instead of being paralyzed by the data you don’t have, you must articulate the precise use case you will solve, and then align your product with the (imperfect) data tier that serves that specific use case.

Bloomberg broke this deadlock in the 1980s through sheer conviction and vertical integration. When Michael Bloomberg left Salomon Brothers, financial data was fragmented across dozens of sources with varying depths and formats. Rather than waiting for standardization, Bloomberg Terminal created its own data taxonomy, then aggressively acquired and integrated data sources to fit this schema. The initial product had significant gaps—many international bonds had no pricing data, corporate actions were incomplete, and real-time feeds were limited to major exchanges.

But Bloomberg’s insight was that traders needed speed and integration more than perfect coverage. This use-case-driven hypothesis broke the deadlock, and they launched with what they had: solid U.S. equity and Treasury data. They built their product around this tier, and its profitability funded the acquisition of deeper data. Within a decade, Bloomberg had transformed from a company working around data gaps to the definitive source of financial data globally.

This use-case-first approach requires what venture capitalist Ben Horowitz calls “wartime CEO” thinking: making definitive decisions with incomplete information and accepting that some use cases will fail while others succeed.

A Data Tier Framework for Practical Use

To operationalize this strategy, you must connect your top-down vision with your bottom-up data reality. Match your conviction in a high-value use case with the practicality of the data you actually have. Here’s the mental model I use when developing data product strategy.

Tier 1: Core Data

Tier 1 represents foundational data elements with broad coverage. For a healthcare data product, this might include basic demographics, primary diagnosis codes, and standard lab results. Products built on Tier 1 data can serve broad markets but offer limited differentiation. Epic Systems built its early success on exactly this principle. Their initial EHR systems focused on capturing and displaying the core clinical data that every hospital needed, nothing more. They didn’t try to be innovative; they focused on reliable capture and retrieval of basic patient information. This “boring” foundation now processes records for 305 million patients globally.

Tier 2: Enhanced Data

Tier 2 includes richer data available for a substantial subset. Examples might include detailed imaging, genomic panels, or longitudinal treatment histories. Tier 2 enables specialized products for defined market segments. For example, Palantir’s Foundry platform doesn’t require perfect data from their enterprise clients. Instead, they’ve built tools that work with whatever data density exists, creating value from partial datasets. For a pharmaceutical client, this might mean combining complete sales data (Tier 1) with partial clinical trial results and incomplete competitor intelligence (Tier 2) to generate market insights.

Tier 3: Deep Data

Tier 3 represents well-connected, well-annotated, high-value data which is typically the least available. Tier 3 data supports premium products for specialized use cases where data depth trumps breadth. Foundation Medicine built a billion-dollar business in this tier by focusing exclusively on comprehensive genomic profiling for cancer patients. They never attempted to serve the entire cancer patient population. Instead, they created a premium product for the subset of patients and oncologists who needed the deepest possible molecular insights. Their FoundationOne CDx test requires tissue samples and extensive processing. This currently limits their test to the ~15% of cancer patients with advanced disease, but for that segment, it provides unmatched value in treatment selection.

The key is to build products for each tier independently rather than waiting for data to “graduate” between tiers.

The Path Forward: Embracing Imperfection

For modern data product builders, especially in complex domains like healthcare, the lesson is clear: there’s no need to build universal solutions. Instead, there’s an opportunity to embrace your data’s natural distribution. Build distinct products for different data depths. Accept that some users need raw access while others need curated experiences. Most importantly, have the conviction to launch with imperfect coverage, knowing that successful products create the momentum for data acquisition.

The question isn’t whether you have enough data to build a product. It’s whether you’ve correctly aligned your product ambitions with your data reality. Get that alignment right, and even the sparsest dataset can support a valuable product. Get it wrong, and no amount of data will save you from building something nobody needs.

As John Snow demonstrated 170 years ago, the power isn’t in the data itself, it’s in understanding precisely what questions your data can actually answer, then building products that answer those questions exceptionally well. Everything else is just noise in the long tail.