· Brian Dranka · Strategy · 12 min read

Connecting Breakthrough Business to Breakthrough Science

When Theranos collapsed in 2016, the wreckage revealed something more interesting than simple fraud. The company had promised to revolutionize blood testing with technology that could run hundreds of tests from a single finger prick - genuine value for patients and physicians which would have transformed diagnostics if they’d actually delivered it. Instead, Theranos became the ultimate cautionary tale: a business model perfectly engineered to capture value from innovation that didn’t exist.

In the life sciences, this underlying tension plays out every day with real technology: the constant push and pull between creating something innovative or useful and actually building a business around that technology. Theranos’s leadership was so blinded by their value capture mechanism that they were unwilling to acknowledge the shortcomings in their value creation mechanism. They failed to see that technological innovation and business model innovation are meant to go hand-in-hand.

The Fundamentals: What We’re Actually Talking About

Let’s start with definitions, because the distinction between value creation and value capture is more nuanced than it first appears. And in my opinion, understanding this nuance is what separates companies that struggle to survive from those that thrive.

Value creation is the process of generating something that has greater worth than the sum of its inputs. In science, this is straightforward enough: build a product or software that improves how research gets done or how patients get treated. Maybe your liquid biopsy platform detects cancer earlier than existing methods. Maybe your proteomics workflow cuts sample prep time from days to hours. The value you create is measured by the difference between the world with your tool and the world without it. This is what economists call “use value,” or the actual utility someone derives from your offering.

Value capture, by contrast, is the portion of that created value that flows back to your company as profit. This is tied to “exchange value,” or what customers are actually willing to pay. And from what I’ve experienced over many companies and product lines, creating enormous value doesn’t automatically mean you’ll capture much of it.

Visualizing the Value Distribution

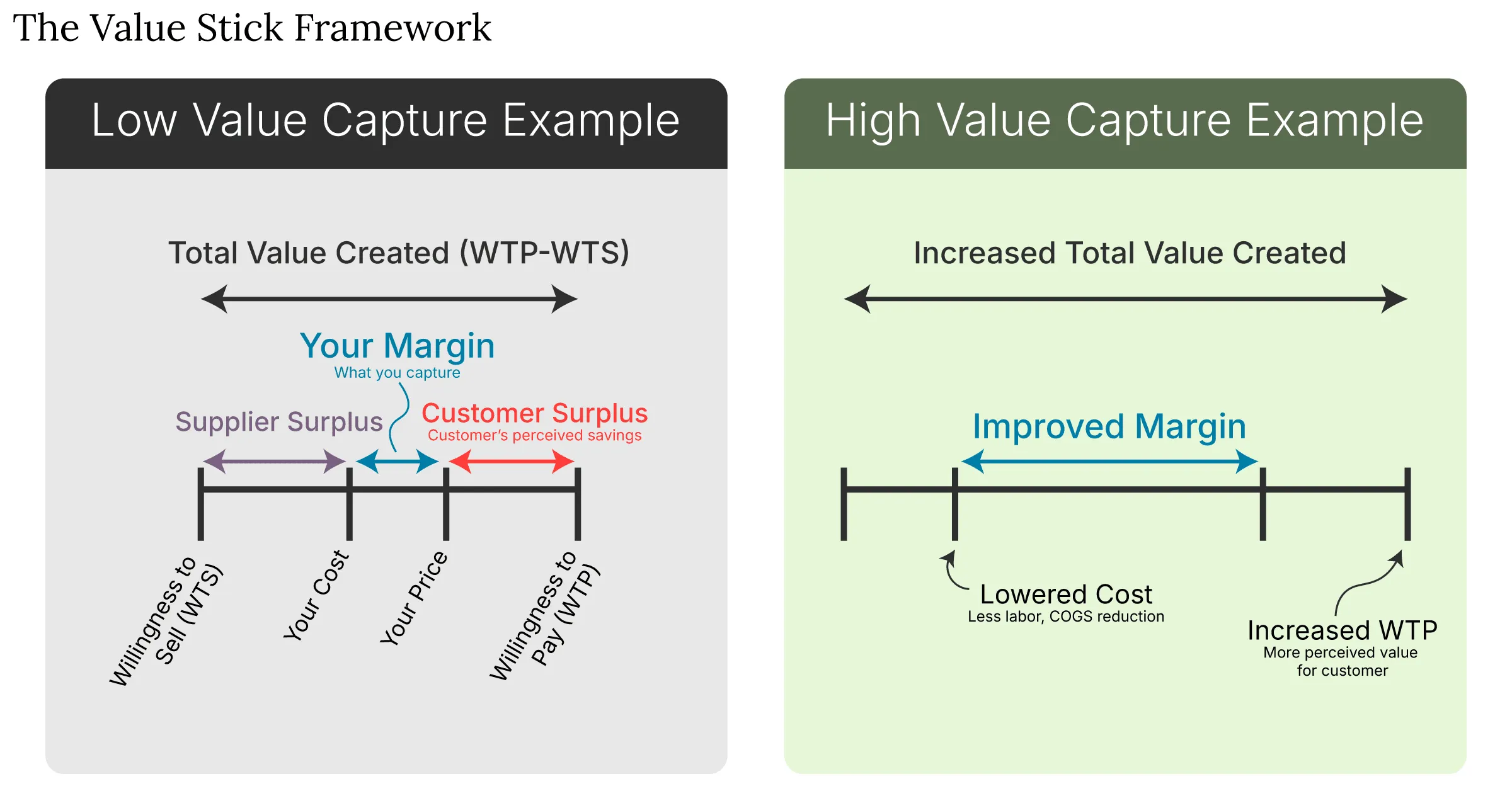

Strategy scholars have spent years covering this topic in better detail than I could here, but I recently read an HBS article by Felix Oberholzer-Gee that I felt offered a clear framework for where the value accrues in a transaction. He calls it the value stick, and while it builds on classic economic theory, the visualization makes the strategic implications crystal clear.

The framework (shown below) works like this: at the top sits the customer’s Willingness to Pay (WTP) - the maximum they’d pay for your solution. At the bottom is your suppliers’ and employees’ Willingness to Sell (WTS) - the minimum they’d accept for their contributions. Your actual Price and Cost sit somewhere in between.

The genius of this model is showing that value gets distributed across multiple parties: customers capture the gap between what they’d pay and what they actually pay; you capture the margin between your price and costs; suppliers and employees capture the difference between your costs and their minimum acceptable compensation. The total value created (the length of the entire stick) is what matters for society. But your margin (the captured value) is what determines whether your business survives.

Why Value Capture isn’t a Guarantee

So why doesn’t value capture happen automatically? If you create something valuable, shouldn’t the market reward you accordingly?

The answer lies in competitive dynamics and what economists call “market frictions.” In a perfectly efficient market with no barriers (where customers have complete information, can switch suppliers instantly at no cost, and face no compatibility issues) competition would drive prices down until companies barely capture any value at all. Every dollar of value you create would be competed away as “customer surplus.”

However, real markets aren’t perfectly efficient, and understanding why matters for how you design a product or solution. The most successful life science companies create comprehensive solutions where the technology is part of an integrated system that delivers sustained value.

When you build an installed base of instruments running proprietary reagents, you ensure consistent performance and validated results that your customers depend on. When you develop a unique technology protected by patents, you secure the returns needed to fund the years of R&D that created the breakthrough. When your platform generates data that becomes more valuable as more people use it, you leverage the network effect to enable reference databases and comparative benchmarks that make your tool more useful to everyone.

Value capture isn’t just about creating something good; it’s about thoughtfully designing an end-to-end solution where customers succeed because of their ongoing relationship with you. This is the fundamental challenge for any life science company developing analytical tools: you must think holistically about the entire value delivery system, not just the core technology. Creating breakthrough technology is necessary but not sufficient. You also need to thoughtfully architect the complete solution (reagents, software, data standards, training programs, etc) that allow you to capture a fair share of the value you create while simultaneously maximizing the value your customers receive.

Done right, value capture mechanisms and value creation mechanisms reinforce each other. Your customers get better outcomes because they’re embedded in your ecosystem, and you capture sustainable returns because you’re delivering those ongoing outcomes. Miss either side of this equation, and you’re building a company on an unstable foundation.

Four Strategic Positions (And Where You Probably Are)

If we plot value creation and value capture on two axes, we get a matrix that defines four strategic positions companies fall into.

Low Creation / High Capture: The Entrenched Player

The entrenched player quadrant is defined by companies living on past glory. These are the established platforms with strong moats. They’re extracting value from past innovation rather than creating much new value today. Think of legacy PCR platforms charging premium prices for basic amplification, or antibody suppliers whose catalogs haven’t meaningfully expanded in years but whose customers can’t easily switch due to validated protocols.

The Entrenched Player is one breakthrough away from irrelevance.

High Creation / Low Capture: The Innovator’s Nightmare

This is where many life science startups die. You’ve developed something genuinely novel. Early adopter labs love it. Papers get published. But inexplicably the business struggles to make money.

The issue here is rarely the core technology. It’s that the company has confused a product with a business model. They’ve created a point solution that’s easy for customers to adopt and just as easy to abandon. The value created in this scenario is transactional rather than relational. There’s a missing ecosystem of reagents, software, and data that transforms a single sale into a long-term revenue stream.

Oxford Nanopore is a fantastic case study in how to successfully navigate out of this quadrant. They spent years in this nightmare quadrant. Breaking free involved a strategic layering of value capture mechanisms. They paired the instrument with a recurring-revenue flow cell, layered in a SaaS-style cloud analytics software package, and have put genuine effort into ensuring their customer base feels the delight that increases WTP. Together these developments built a sample-to-answer workflow and a moat to defend against would-be competitors all while improving the customer experience.

Low Creation / Low Capture: The Commodity Trap

The commodity trap is the brutal middle of mature markets. Basic ELISA kits. Standard Western blot reagents. Routine genetic analyzers. Limited differentiation means intense price competition, which prevents meaningful profit margins.

You might be surprised how many life science companies drift here without realizing it. Your product was innovative five years ago, but now there are a dozen similar offerings. You’re competing primarily on price and delivery time. If this is you, you need to either re-innovate (move up on the creation axis) or find capture mechanisms that don’t depend on product differentiation.

High Creation / High Capture: The Strategic Ideal

Finally we have the strategic ideal where the most admired life science companies operate. They continuously create genuine value through innovation while simultaneously building robust mechanisms to capture that value.

10x Genomics exemplifies this. They created real value with their single-cell sequencing platforms—researchers can now see cellular heterogeneity that was previously invisible. But they also built powerful capture mechanisms: proprietary reagent chemistries that customers must purchase repeatedly, integrated analysis software that increases switching costs, and a patent portfolio that limits direct competition. They’re not just selling instruments; they’re orchestrating an ecosystem where value flows through their platform.

Just know that this ‘ideal’ state is not a safe harbor, it’s the eye of the storm. High margins attract a flood of venture money to competitors on a mission to break your lock-in. Proprietary reagents are seen by customers as an expensive tax on their science. An ecosystem can be viewed as a monopoly by regulators. This is not a place to rest on your laurels.

The Capture Question: It’s Not Just Pricing

When life science companies think about value capture, they often jump straight to pricing strategy. That’s important, but it’s incomplete. Real capture happens through business model design.

Recurring Revenue Beats One-Time Sales

If you’re selling analytical instruments, you’re probably thinking about this already. The instrument sale might have a healthy margin, but the real value capture happens through consumables. Flow cytometer manufacturers learned this decades ago: competitive instrument pricing to win placements, then sustained profitability through antibody panels, calibration beads, and maintenance contracts.

But you can push this further. What if instead of selling instruments at all, you sold outcomes? Suddenly, you’re capturing value proportional to usage, you control the entire service delivery, and your customers have predictable costs. This is why core facilities and CROs are often better businesses than equipment manufacturers.

Ecosystem Lock-In Creates Sustainable Capture

The most defensible capture mechanisms in life sciences come from building ecosystems where your platform becomes infrastructure. This means:

- Workflow integration: Your tool shouldn’t be a standalone solution; it should be embedded in validated workflows that are painful to change

- Data network effects: The more users you have, the better your reference databases, which attracts more users

- Switching costs: Training, validated methods, regulatory documentation - each adds friction that protects your value capture

Illumina’s dominance isn’t really about having the best sequencing chemistry. It’s that they’ve built an ecosystem where switching would mean revalidating protocols, retraining staff, redoing comparisons to published data, and potentially re-submitting regulatory documentation. That’s a $500,000 question that most labs answer by staying put (but get your popcorn out because Roche, Element, and Ultima are all gunning for a slice of this giant pie).

Lowering Willingness to Sell (Not Just Raising Willingness to Pay)

Here’s where the Value Stick framework becomes really useful. Most life science companies obsess over raising customers’ willingness to pay through better performance, new applications, stronger data. That’s value creation, and it matters. But you can also capture more value by lowering your own costs without cutting corners.

The insight: your suppliers and employees have a “willingness to sell” (WTS) which is the minimum they’ll accept for their inputs. If you can provide non-monetary value that lowers their WTS, you capture more margin without squeezing anyone.

For suppliers, this might mean longer-term contracts that give them planning certainty, or technical support that helps them improve their own processes. For employees, it’s the difference between a sweatshop biotech that burns through scientists and a company known for strong training, reasonable hours, and clear career paths. The latter can often hire better talent at lower cash compensation because they’re providing value beyond salary.

A Diagnostic: Where Are You Really?

Let’s make this practical. Ask yourself these questions:

On Value Creation:

- If we disappeared tomorrow, would our customers genuinely struggle to do their research, or would they just switch to a competitor?

- Are we creating value through genuine innovation, or are we capturing value from a historically strong position?

- When was the last time we enabled a research workflow that was previously impossible?

On Value Capture:

- What percentage of our revenue is recurring versus one-time?

- How much would it cost (in time, money, and risk) for a customer to switch from our solution to a competitor’s?

- Are we selling products, or are we selling outcomes?

- If a customer builds an in-house solution, do we capture any of that value?

If you’re creating substantial value but struggling to capture it, the answer usually isn’t to create even more value. It’s to redesign your business model to include capture mechanisms from the start.

The Real Challenge: Organizational Alignment

Here’s what makes this difficult in practice: your R&D team is naturally focused on value creation. They want to build the best technology, enable new science, and get publications. Your finance and sales teams are focused on value capture: pricing, margins, quarterly targets.

This necessary tension needs to be managed. Your product development roadmap should include both creation and capture features. Yes, develop the breakthrough application that will wow researchers. But also develop the sticky integration, the proprietary reagent, the validated protocol that makes switching costly.

The companies that win don’t just create better tools. They create better tools embedded in business models that ensure they profit from those innovations. That means your early-stage decisions such as pricing model, IP strategy, supply chain design, software architecture should consider capture from day one, not as an afterthought.

Final Thoughts

In life sciences, creating value is table stakes. Every startup is trying to make research faster, cheaper, or more accurate. The ones that build enduring businesses are those that also master the discipline of value capture through thoughtful business model design.

And if you’re currently in that painful position of creating genuine value but struggling to make money from it, remember: you’re not alone, and you’re not doomed. You just need to innovate your business model as aggressively as you innovate your technology. Sometimes, that’s the harder problem to solve, but it’s also the more defensible one.